A History of Elysian Park’s Victory Memorial Grove

By Courtland JindraA Flag Day ceremony at the Victory Memorial Grove in 2019.

After the First World War, American communities large and small struggled with how best to remember their fallen. Large memorials built by the federal government were uncommon a century ago, so local and state leaders took up the slack. Debates emerged between those who favored statues and monuments in the traditional style and others who championed the idea of “living memorials."

Los Angeles was much the same. Over 23,000 Angelenos had served in the armed forces. Of those, more than 450 had made the ultimate sacrifice. Debates on how best to honor the troops had become heated among civic organizations and city officials alike. Eventually, a variety of memorials was dedicated throughout the area. Across the nation, parks were a popular way to remember the fallen. In Southern California, the Los Angeles Examiner promoted this idea. It’s difficult to determine exactly how much influence the newspaper had, but just prior to Memorial Day 1919, the Examiner offered the following resolution in writing to the L.A. Parks Commissioners, which adopted it unanimously on May 29, 1919:

"WHEREAS, "The Los Angeles Examiner" has suggested that a Victory Memorial Grove of trees be planted on property of the Los Angeles Park Commission and be perpetually cared for by the Commission in recognition of the sacrifice made by Los Angeles heroes in the cause of liberty, and

WHEREAS, The site for the proposed Victory Memorial Grove has been selected as a hill in Elysian Park and thereby lends itself easily to watering and other practical features of cultivation; is readily accessible, and is a location which, by reason of its altitude, would allow the living green memorial to be seen at all times by the residents of Los Angeles and visitors, therefore be it

RESOLVED that the members of the Park Commission formally agree on the site;

AND WHEREAS; it is deemed that the most suitable occasion for the dedication of Victory Memorial Grove is Memorial Day, May 30, and in the forenoon of that day so as not to conflict with the Memorial services already planned for the afternoon; and that a start should be made by Los Angeles, in keeping with the movement which has taken hold in cities over the nation to honor their heroes with this simple and befitting means, so that in future years the people of the city may have the opportunity of doing honor to, and commemorating the deeds of, its heroic dead, therefore be it further,

RESOLVED; That the members of the Park Commission undertake the presentation of a dedicatory program on the morning of Memorial Day, to comprise such features as a dedicatory address, responses, community singing and the planting of the first tree, or other such exercises as the members see fit to plan, in order that the custom of the years to come may be ushered in, and that the people at large may begin to look upon Victory Memorial Grove as a place of reverence to be more beautiful each year.”

The chosen location was what is today Radio Hill. An initial tree was dedicated and hopes were high for the future of the site. The park’s archives are full of inquiries into tree plantings at the Memorial Grove. Land surveys were completed, but there was a problem with access to the new park. Within a year, frustration seemed to boil over since nothing had been done besides the initial tree being sown. President of the Parks Commissioners, Leafie Sloan-Orcutt, eyed another site for this "Victory Memorial Grove.”

A Local Angeleno Takes the Lead

Mrs. Mary Stilson, who spearheaded the effort to establish Victory Memorial Grove and donated land at the grove’s entrance.

Mary Stilson was a mover and shaker in early twentieth century Los Angeles. She became deeply involved in real estate after her husband died with massive land holdings in 1888. Along with her son, she developed many areas around what is today central Los Angeles, including Angelino Heights.

Stilson was also active in civic organizations, including Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). She had earlier been State Regent and was still a well-placed member in the years following the war. In March of 1920, the DAR state officers decided they wished to honor the "memory of those who had served in the World War from the families of the state organization." DAR especially sought to recognize those who gave their lives to the cause. Women from the southern part of the state formed a committee to take on the mission to bring this project to fruition. Four local L.A.-area chapters took the lead in raising money and getting a plaque made. Though the committee was based in Southern California, the entire state's membership was represented. Given that some of the relatives who perished in the war lived in other states, it was destined to not just be a state monument, but a national or even international one. (A British Naval Surgeon who lost his life at sea had a sister in the organization and was included.)

Stilson didn’t lead the memorial committee, but soon after its formation, the group received permission from the Parks Board to place a monument at Victory Memorial Grove—a decision likely influenced by the fact that the Mayor’s wife, May Snyder, was a member of the DAR—and requested a walk-through of the site. Were the ladies displeased with the location? Did Sloan-Orcutt ask them to consider a new site, or did they approach her? That part of the story has been lost to history. What is known is that by July, Stilson had donated part of her land holdings off Lilac Terrace to the Parks Board.

At a late July meeting of the Park Commissioners, William Bowen exploded, "We were bamboozled when we had that site 'wished' on us by the Examiner," and felt "like apologizing to the City Council." Mrs. Sloan-Orcutt retorted: "It was a perfectly good site, only we found out that we could not buy a lot for an entrance so we could get into the park...we are going to dedicate the new one next Monday afternoon at 3 o'clock too."

And so they did. On August 2, 1920, the current Victory Memorial Grove was established with the planting of three oak trees. Stilson’s land formed the entryway to the grove. One tree was planted by Mayor “Pinkie” Snyder in honor of his son, Captain Ross Snyder; another by Mr. Otheman Stevens for his wife, Elizabeth Stevens, who created the Red Cross salvage system to raise money for the war effort; and a third by Lieutenant Buron Fitts on behalf of the American Legion, in honor of all those who lost their lives in the war.

A Space to Pay Respects

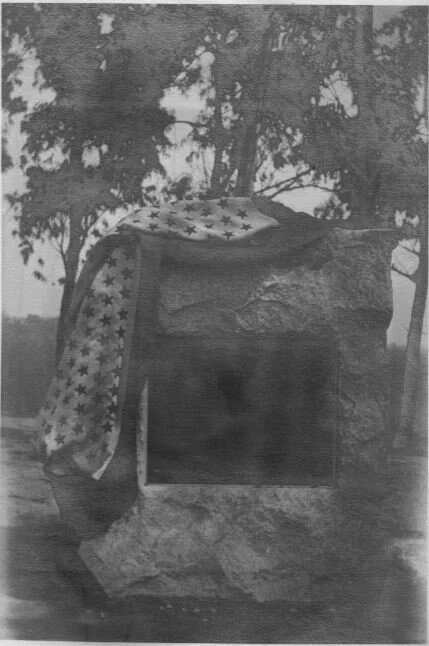

The original dedication in 1921.

Once the new site was established, improvements came much more quickly. On Armistice Day 1920, poppy seeds from Flanders were sown by members of the American Legion as well as residents of the area. Walking paths were designed and a flagpole was planned to be put in the ground so that "people, when they visit the spot, will know and appreciate it." More trees were planted, including thirteen bought by Captain Walter Brinkop, one for each of the men who lost their lives under his command. A plaque for the entryway of the site was designed by local sculptress Julia Bracken Wendt, but was unfortunately never cast in bronze.

Meanwhile, the DAR ladies quickly raised the necessary funds and moved forward with erecting their monument. The granite marker was from a California quarry and the chiseling was done by the Lane Brothers, a local company of the time that specialized in stonework. The bronze tablet was designed by artist Mr. W.A. Sharp. Besides the twenty-one names listed (there is one omission due to Frank Davis's mother not getting his name in before the deadline to cast—he was instead remembered in the dedication program and booklet), six shields sit on the borders. They represent the Army, the Navy, Aviation, the Red Cross, the state shield, and the insignia of DAR. Above everything is an eagle, the national symbol of guardianship. With much pomp and circumstance, the monument was dedicated on Flag Day, June 14, 1921. In her opening speech, State Vice-Regent Margaret Powell Stookey declared:

"Here high on this beautiful hillside we have chosen a spot for our memorial--high above the life and turmoil of the city, glimpses of which we see though the protecting hills, our boulder stands and carries its message to the World--our thanks to our loved ones expressed in this simple way. High enough it stands that the sun in the morning touches it with its rays of promise and keeps it ever in a flood of light until the great golden ball sinks into the sea at the close of day--and back of it the towering strength of our wonderful mountains--the whole setting symbolic of their lives and deeds--towering strength and protection, blessings given, promises fulfilled and the close of day here only meaning the continuation of the Day Elsewhere."

Music was played, a poem was read, more speeches given and, finally, the monument — which had been hidden by a massive service flag — was unveiled. Though it was fittingly an overcast day given the somber proceedings, it was also a moving one. At the end, Mrs. Stookey took the lectern again as she bestowed the monument to the City of Los Angeles for their caretakership. In her closing remarks she stated, "This is but an outward expression of what is in our hearts and may we establish the custom of a pilgrimage each year to this spot to pay tribute to these who were our great friends and benefactors.”

With that Mr. Conaway, assistant to Mayor Snyder, accepted the monument on behalf of the city.

The Los Angeles Times seemed to believe that Flag Day would be a day of tributes at Victory Memorial Grove going forward, writing “Undoubtedly as other flag days come other memorials will be erected, thus making the grove one of the fine memories of patriotism.” Memorial trees continued to be planted for years after the park's establishment. The trees themselves were free of charge, but loved ones had to pay $50 for the plaques required to accompany them, a considerable sum at the time. It is difficult to determine exactly how many trees were planted at Victory Memorial Grove as the archives are skeletal, but what documents do exist indicate that there were more than forty. It's also tough to know when exactly memorial tributes and/or ceremonies ended at the park, when the monument became ignored, or when the Grove itself fell into disrepair.

A Renewed Appreciation for the Victory Memorial Grove

Members of the Friends of Elysian Park plant new trees at the Victory Memorial Grove in 2018.

Since 2017, several civic organizations including the Los Angeles-Eschscholtzia DAR, Hollywood Post 43 of the American Legion, and the Friends of Elysian Park, first worked on restoring the monument and grounds immediately surrounding it. Then the movement moved toward the park as a whole. Efforts have included replanting trees, fixing the historic flagpole, cultivating various native plants and generally reviving the space.

It has also become a yearly tradition to mark Flag Day at Victory Memorial Grove. The idea is not to just honor those listed on the monument, but all the doughboys, nurses, sailors, and others who died in the First World War. Without us, the living, memorials are just forgotten parcels of land and ignored stones or plaques. We give them their purpose. Elysian Park was created for recreation, but Victory Memorial Grove was—and remains—a place for reflecting on the immense sacrifice of the First World War, which claimed more American lives in just 18 months than both the Korean and Vietnam Wars combined. That’s why we continue to gather at the Grove each year—to honor that sacrifice and ensure it is never forgotten.

We invite you to join us annually on Flag Day as we pay tribute to those who gave their lives over a century ago.